---

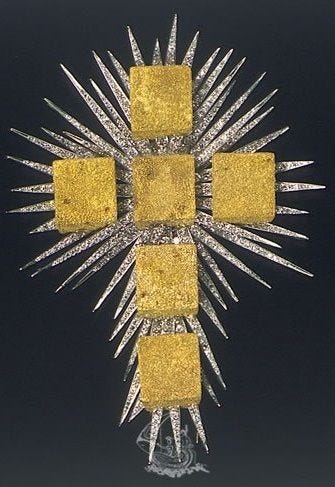

To me, there is no more melancholy beauty than the sight of that frail golden glow emerging from the gloom, like a sunset on the distant horizon. I have walked past such a sight, only to return again and again, for as one moves away, the gold on the paper’s surface glows even brighter. Not in a busy flickering, dazzling way, but steadily over time, like the changing complexion of a giant’s face. As one moves away, we suddenly discover that what was initially the rather dull reflection of the gold leaf begins to gleam as if on fire, and we are faced with the mystery of how so much light is able to be found in these dark reaches.

Now I understand why the ancients gilded the statues of Buddha in gold flake and the nobles papered the walls of their homes with it. Living in brightly lit homes, it is hard for us to truly understand the beauty of gold. But for our ancestors, living in darkness, it was not just an enchantment with the metal, but a choice that had practical value as a reflector in a room with limited light. In other words, they saw the use of gold and gold flake not as a luxury, but as a way to compensate for the lack of light. What seems to be their strange fixation on gold is explained by the fact that silver and other metals lose their luster, while gold retains its ability to illuminate the darkness with its brilliance for a very long time.

Earlier, I wrote that lacquerware decorated with gold was meant for viewing in dark places. It’s now known that the same motive was behind our ancestors’ use of gold thread in textiles. The gold brocade of monks’ stoles is the best example. Today, the main buildings of most local temples are well lit in order to appeal to the masses, and such garments will appear vain and garish, of little virtue regardless of the high priest’s character. But if one attends a Buddhist rite at one of the historic temples that follow the traditional style, one will notice how well the gold harmonizes with the wrinkled skin of the elderly priest in the flickering light of the candle offerings, and how it brings solemnity to the occasion. As with lacquerware, most of the gaudy pattern is concealed in the darkness, and the gleam of the gold and silver threads appears only now and then, in brief, fleeting moments.

- Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows

---

Junichiro Tanizaki lived through the modernization of Japan. The abrupt shift from pre-industrial to electrified aesthetics left a strong degree of culture shock. Tanizaki saw changes that were too imperceptible in our more incremental western transition. This is perhaps most significant as it comes to historical religious aesthetics with use of gold and lace once deeply affecting, now strange in the light of modern conditions. The divergence between the intent of continuity and the practice gives a guide towards an eternal aesthetic.

I think it is a common experience, that you walk in to some cathedral or church, and you see the cultivated aesthetic, one of gold and fine art. The same gold and the same background that has been there for hundreds of years, and somehow it looks cheap. One may wonder how such a sight could ever inspire awe. Despite this attempted continuity with tradition, something critical has changed, and the answer is above you. For a change this isn't a spiritual remark but is referring to the harshness of modern lighting.

Gold is a peculiar metal, thought of as the untarnishable metal, it was the standard of value for most of human existence until 1971 when the United States terminated dollar to gold conversions. The etymology of the Latin "aurum" stemming from glowing. As Tanizaki says, it can sit in the shadows and drink light in, leading to this captivating glow. You have to imagine these ritual scenes yourself. The darkness of the church, lit only by flickering candles. The shifting lights fading into the blackness around, except for the altar, where all the light in the church is pouring into the golden adornments. The priest facing the altar, the gold inlay on his back absorbing the light in the same way as he goes through his motions. Coupled with the smoky atmosphere from the incense, it was a unique experience for a people who for a time had so much plainness elsewhere. Now fully illuminated in bright white light, the gold can only look reflective at best, taking on another tacky shiny look that modern culture has become numb to.

In a similar vein, lace was once a monument to human labor. When the fine detail was done by hand, an inch of lace could take an entire day, slower for some of the finest detail work. You can imagine the cost implications, and the significance was well understood culturally. When they saw a priest in lace vestments, they understood that he was wearing a year's worth of labor, that there was enough importance in the religious life that someone had done so. Post mechanization, lace became trivial to manufacture and as with so many once high status obtainments, it flew down the social hierarchy. Today excess lace is considered the domain of somewhat déclassé women, more than any monument to status. This is a more complex problem than the technical erosion of gold's significance, as the cultural moment is far harder to recapture. Lace being a product of the 16th century, this is hardly essential to classical religious aesthetics, but it's worth highlighting as an example of context preventing an authentic recreation.

It is the centrality of life that is shown in these aesthetics. By funneling money and time into religious rituals it shows the primacy of God in the culture. This primacy is how you can see cathedrals that took centuries to build, crafts that move beyond economic sense, and monuments that last generations. This works well when investment and aesthetics are linked, but becomes more challenging as these concepts become divorced. It is particularly challenging as a culture's sense of value and beauty becomes fragmented. What was once all things to all people can struggle to find a universal appeal through aesthetics alone.

The appeal of visible wealth hasn't vanished in America. You could picture a service today making use of this concept. The priest could roll up in a loud sports car, get out wearing lots of gold chains and bracelets. Maybe even a diamond grill on his teeth. All of the money spent on showing the value of the priest. After all, the gold and sports cars don't belong to him, he is merely the custodian to show the importance of God. This would appeal to a disturbing number of people, but if you are reading this, probably not you. It would be unfashionable. Unfashionableness in the truest sense is a failure to recognize the collapse of as prior context. Like the lace wearer who overdoes it past the point of mass availability, someone who is "blinged out" doesn't understand where true value lies today.

Coming to the crux of the problem. If we want to define an aspirational aesthetic, we have to try and determine what is aspirational. A question easier asked than answered in America. We have established one type of American aspiration, but vulgar consumption is a minority, at least pending severe collapse. As a loose observation, the 20th century marked the shifting of American aesthetics from education to entertainment. The emphasis on schooling and literacy, academics, citizen scientists, and the like. You had clergy who could be professors, think Fulton Sheen with his chalkboard. An educational church that placed heavy investment into seminaries and intellectual developments. Whether this successfully marked the church as a fashionable entity is another question. In the turn to entertainment, clergy fashions imitate television personas and Youtube stars. It's not possible to say that in a non disparaging way, but it's not intended. It's natural to see the popularity of certain forms and structures, and think that you can help more people by imitating that. The issue is that while at least academics were nominally well regarded, pundits and entertainers were not, and chasing after an already failed aesthetic may not have had the best results.

What then is the aspiration of the future? As we burn through these different priorities we have less and less left. Material, intellectual, and psychic (which is to say attention), are all rapidly falling by the wayside. The people who survive such a shift are going to have a need for the spiritual. The lightness of Christ in a world of crushing weight. It is a lightness that stands stark in our age of heavy compulsion. Consumption in our culture centers far more around dependency than joy. Addicts, whether they are numbing with drugs, cheap dopamine, or just endless distraction, get little pleasure from their activities. It takes a liberation from compulsion to be able to enjoy what life has to offer. Being able to experience this joy, free of compulsion, gives a small window into the meaning of the lightness of Christ.

This lightness is the most challenging aesthetic to cultivate because it cannot be faked. You can picture a religious leader who attempts to pursue this lightness, dressing without finery and pretending towards austerity, but heaviness and entanglement in his heart will always shine through and repulse people with its falseness. Lightness is compatible with great stewardship, no matter how unfashionable or challenging, but it can never be compatible with an anchored soul. A mere hatred for the material can be a sign of something much darker. True lightness is the possession of interior freedom to such great extent that it overflows to others. It is something that dovetails well with some of my earlier writings on the potency of renunciation as a demonstration of value.

---

The vow of celibacy permits him to take no wife and father no children, thus preserving an undivided heart for the sake of his God. This is what allows the twin vow of poverty, because with no wife and children he has no obligation to feed or preserve anyone. If he needs to starve to death or enter the fire for the sake of his faith he can. The deeper manifestations of these vows for the itinerant preacher are profound. One of the struggles of the church at the time was against the Cathar heresy, who’s “perfects” would practice celibacy, and poverty, going so far as to not even eat meat or any such thing that could be desired by another. You can imagine the difference that a preacher has when they desire nothing from those they preach to. With no desire to take the wealth, food, or women of those they preach to, their motivations can be treated as more sincere. The accusation that they are only in it for the money, or the rich foods, and other fine things falls short in the face of such austerity. The foundation of the Dominican and Franciscan orders provided an important counterbalance of true austerity coupled with true doctrine.

---

---

Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they? Matthew 6:26

---

This lightness of Christ stems from this great renunciation of the world. This is not to say that one must be entirely without possessions, but that one strive to be unburdened by them. In a world in which even the richest are dragged down by material obligations and desires, this lightness is fully aspirational. An aesthetic centers around this lightness looks quite different. It is not the towering cathedral, or the ornate craftswork, but the itinerant Christian carrying the temple of God inside him.

Similarly, there is no music that can be totally aspirational. The only novel sound in a culture of noise is silence. You can see the indications of silence becoming aspirational everywhere. To not suffer interrupting advertisements is a premium, higher end goods having more and more noise canceling. This silence is an aspect of the sabbath, and the demonstration of the need for rest and digestion.

---

The Lord himself demonstrates the necessity of this with the seventh day of creation where work that is done externally must then be done internally. It has to be properly reflected and synthesized inside, and this is the purpose of this day of rest. Without this inward turning, there is this denial of humanity and spirituality. This is why you see it in forced labor programs where people begin to have their humanity reduced, and you even see it in specific torture techniques where rest is explicitly denied in order to reduce the person and make them more breakable. This is an important theme, that the importance of rest and synthesis, and those who seek to deny it to others and those who suffer the consequences of denying it to themselves. Not to get too far ahead of ourselves here but you can see this in present day with those who renounce rest, renounce the sabbath, and choose to be fueled by some digital and chemical concoction and what happens to those people in the long run.

- The unpublished book, that could use some edits.

---

It is not a coincidence that as a post-Christian society exhausts and erodes itself, that the aspirational aesthetic it returns to is the original aesthetic of Christ, and his forebears. There is no material possession that can match unencumberance. No sound that can match silence. No outer trappings that can replace a true interior life with God.